“Knife” #3: Money to Make Art?

“A Knife in a Gun Fight”: Independent Film Money

Finance It, Fund It, or “Fam” It?

by Michelle Kaffko

~~~~~

“A Knife in a Gun Fight” chronicles filmmaker Michelle Kaffko’s journey as she probes the Chicago-area independent scene for indie movie news, releases, and other relevant dirt.

“Production Assistants and other crew needed for 7-day shoot, 8-hour days, NO PAY, but credit and meals provided.”

Commonplace in the trades and on Craigslist, advertisements like the above have become a kind of hazing ritual for newbies wanting to break into “the biz,” including the Chicago independent film scene. Should you pursue the opportunity and your dreams, how many sets do you work on for free until you realize you need to get a real job that pays you in actual minted currency?

Most independent film producers, directors, and other key players spend their days taking important phone calls to book locations and rent equipment in between pouring lattes at their prominent Starbucks day jobs. On-screen credit and food is what most participants receive as reimbursement in this town – the food usually being pizza and not the good deep-dish Chicago pizza – so everyone wants to be “above the line” in the imaginary budgets, clamoring for producer or director titles.

I once had a guy call me while I was in post-production for a short film I directed to demand producer credit … just for loaning me a camera.

But even with a small army of actors and crew willing to put their hard work and hours in for cold pizza, making a film still costs money. Filmmakers know that currency is no myth because they’ve seen it sprout from the billfolds of friends and strangers, so the inevitable question becomes, “Where do I find that money to make my film?”

“Find” is an appropriate word, because funding an independent film is kind of like an Easter egg hunt. You poke around the yard, crossing your fingers until you’re lucky enough to nab yourself an egg … and hope to not step in some dog doo in the process.

I’ve heard many a horror story involving money and movies. My favorite urban legend, told around the campfires of film school campuses, concerns the guy who shot a film in a steakhouse and unplugged the refrigerator in the kitchen so he could record cleaner sound. No one remembered to plug it back in, so the steakhouse owners returned the next day to find $10,000 worth of ruined prime rib and t-bones. The filmmaker had to pay for them. The moral of the story is to “put all the crew members’ car keys in the unplugged fridge so some moron will remember to plug it back in before leaving,” as a veteran AD might be heard saying to a freshman PA at the craft table.

Between the tall tales of grandiose blunders, I’ve also heard how several local films were successfully funded. And by successfully, I mean someone wanted to make a film, needed the money, actually found the money, and then made the film. That alone can be a superhuman feat. Let’s now zero in on the three most prevailing methods of finding money that I know: financing, funding, and “fam.” That last one can also be called “rich Uncle Bill,” but “fam” starts with an “f” like the others so I’m going to use that.

By financing a film, I’m talking about approaching investors for the money to make the movie. An investor is someone who is usually outside the film industry but has enough of an expendable income to take a risk on an independent film. And monetarily it can be considered a bigger risk than the stock market, even in this volatile economy. Many investors are promised a percentage of the profits of the film to return their investment if the film lands a good distribution deal or makes money in any other way. Most receive credit in the film, usually as Executive Producer.

The Easter egg hunt to find these investors and convince them to write you a check to make your next zombie movie can be a full-time job. (I mean, come on, would you give someone $300,000 of your hard-earned cash to film people pretending to eat other peoples’ brains? If you would, e-mail me. I have a killer script for a zombie film…) Filmmakers seeking investors need to prove as well as they can that their film is worthy of being made and can turn a profit. In the world of financing, your film isn’t a film. It’s a start-up small business. An investor needs to see a comprehensive business plan that lays out why the film will be successful, who will watch it, who will distribute it, and how much money it is projected to make based on the successes of similar films or films with similar stars, directors, and/or producers.

Independent filmmaker and actor Tom Malloy (LOVE N’ DANCING) lays out the skeleton of the process of hunting, spearing, and skinning investors for their pelts in his book, Bankroll: a New Approach to Financing Feature Films, a current release from Michael Wiese Productions, the long-time oasis for movie producers seeking books and guides covering all the different processes behind making movies. (Downstate readers will be happy to know that Wiese himself is an Urbana native, University of Illinois alumnus, and former classmate of Roger Ebert!) In Bankroll, Malloy tells his own steakhouse horror stories and other lessons he has learned while raising millions to fund indie feature films, detailing several different approaches for finding and securing investors vividly enough that you might find yourself looking over your shoulder while reading the book to make sure no one else is gleaning the secrets along with you. The author’s methods are intended for productions in the $2-$5 million range, but his advice in dealing with industry people can be helpful even to unpaid PAs eating cold thin crust pizza.

Independent filmmaker and actor Tom Malloy (LOVE N’ DANCING) lays out the skeleton of the process of hunting, spearing, and skinning investors for their pelts in his book, Bankroll: a New Approach to Financing Feature Films, a current release from Michael Wiese Productions, the long-time oasis for movie producers seeking books and guides covering all the different processes behind making movies. (Downstate readers will be happy to know that Wiese himself is an Urbana native, University of Illinois alumnus, and former classmate of Roger Ebert!) In Bankroll, Malloy tells his own steakhouse horror stories and other lessons he has learned while raising millions to fund indie feature films, detailing several different approaches for finding and securing investors vividly enough that you might find yourself looking over your shoulder while reading the book to make sure no one else is gleaning the secrets along with you. The author’s methods are intended for productions in the $2-$5 million range, but his advice in dealing with industry people can be helpful even to unpaid PAs eating cold thin crust pizza.

Kevin Brennan and his partners used financing to back their film, THE SCENESTERS, which is bouncing along the festival circuit, recently winning Best Comedy in the Hollywood Film Festival and scheduled to play Slamdance next month in Park City, Utah. A comedy about bumbling crime scene investigators and staff following a serial killer to make a film about him under police radar, THE SCENESTERS is the creation of Los Angeles-based comedy troupe The Vacationeers whose members include SCENESTERS writer/director/actor Todd Berger as well as three former Second City-Chicago classmates: producer Brennan, producer/actor Jeff Grace, and actor Blaise Miller. The project’s other producer, Brett D. Thompson, still lives in Chicago.

Before filming, they sent a 15-page business plan to friends, family, friends of friends, and anyone they could find who’d be interested in investing in the project. “It had everything from cast and crew bios to box office projections based on similar films,” Brennan explains. “Part of the idea came from my film school classes at the University of Texas at Austin. But most importantly, we wanted investors to know that we were serious about taking care of and using their money.”

Their business plan worked, helping them raise 100% of their budget through investors before going into production, and they had enough foresight to tack a 10% contingency onto their total budget (estimated at less than $1 million) to cover any unexpected expenses. “Thank God we did,” says Brennan, since their film, like many, had plenty of unexpected expenses. Even though their budget was handled business-like, actually making the film qualified as a labor of love for the filmmakers, cast, and crew with the “above the line” members deferring their payment until the film sells and turns a profit. Brennan is currently in talks with distributors.

Technically, the filmmaking team at Split Pillow has investors for their projects as well, but they’re investing in Split Pillow itself and not the individual films. As a non-profit entity, they use funding and not financing to make their films, averaging about one feature per year. “The mission statement [of Split Pillow] is to develop and promote the work of Chicago filmmakers,” explains Executive Director Dennis Belogorsky, another UIUC grad and an early member of the school’s Illini Film & Video club. “The secondary mission statement is to create a film culture in the city that can sustain itself and feeds itself and draws inspiration from within, not from without.”

Split Pillow’s non-profit status also means they are eligible for grants and more likely to get money through those grants for sponsoring community outreach programs, such as their youth workshop Media START!, which promotes media literacy by teaching groups of children how to write, direct, shoot, and edit their own films and tell their own stories. By having such community components in their filmmaking group, Split Pillow is able to find about 95% of their operating budget through grants and donations.

Said donors aren’t necessarily considering themselves as investors in individual films, expecting a financial return on their investment. They give generously because they like the group they’re giving to; for instance, the annual Split Pillow fundraiser last October earned about $20,000 for their operating expenses. Meaning, the part-time members of Split Pillow can actually get paid for their work in the group and they can make films, a double-whammy superhuman feat in this world. Their latest feature, EYE OF THE SANDMAN, follows a one-eyed bride-to-be who obsesses over a mysterious stranger which threatens the wedding and her newly inherited home.

But what do you do if you have a film you really want to make but don’t want to do the work of becoming a non-profit to attract funders and don’t really know where to begin to attract investors for financing? This is the Easter egg I call “fam” because that’s where most of these filmmakers will turn once their own wallets empty out into a film – their family.

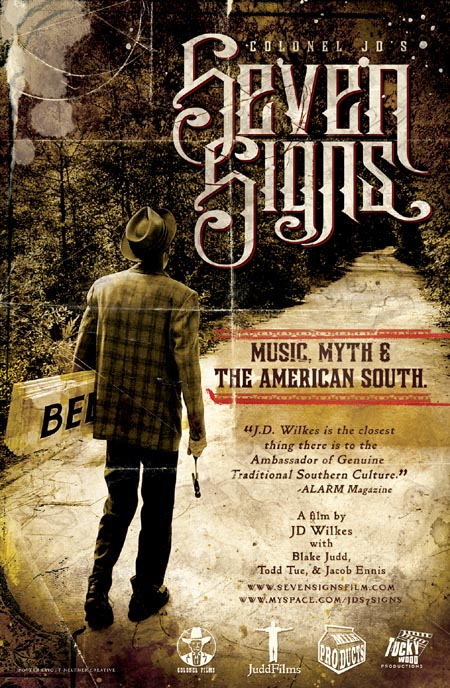

Filmmakers Todd Tue, J.D. Wilkes, and Blake Judd made their film, SEVEN SIGNS: MUSIC, MYTH, AND THE AMERICAN SOUTH, with very little pre-production or budget creation. SEVEN SIGNS is a documentary about a cultural niche in the music of the South, for which the team “just started taking road trips in J.D.’s car, staying at friends’ houses and borrowing equipment” to get it made, as Chicagoan Tue describes. “We knew we were going to fund it personally up to a certain point, and then we planned to approach friends and family for investments and/or donations, which is what we did.”

Tue estimates that about 65% of the money to make SEVEN SIGNS came from the filmmakers themselves and 35% from others. In their “fam” model of film funding, they hit upon the best of both worlds with financing and funding by engaging investors who are also close friends and family happy to fund their quest to make the film itself. Of course, the trio did make agreements with them to share profits if the film turned one, but they also didn’t have to prove themselves through lengthy budget estimates and a best-case-scenario business plan promising huge returns on investments.

Now that we’ve compared the money-hunting methods of three projects that start with the letter “s,” here’s another “s,” success. How do you measure the success of any of these projects? Almost every independent filmmaker in the Midwest creates his or her project with the hopes that it will be the greatest thing since sliced bread, but the truly successful filmmakers are those who will make the film anyway – regardless of how much financial investment will come back later.

The aforementioned Bankroll demonstrates how author Tom Malloy successfully made his living financing his own film projects and supported his family quite comfortably. So, turning a financial profit on independent films is possible and not just a pipe dream. It’s simply a long and tiring journey of Easter egg hunting to get there, avoiding all the dog doo on the proverbial lawn. Malloy cites a joke in his book that can make plenty of indie filmmakers laugh and cry at the same time:

“How do you make a small fortune in independent film? Invest a large fortune.”

~~~~~

THE SCENESTERS is a production of Johnny Voodoo Productions in association with Vacationeers Productions and Midwinter Studios. It was written and directed by Todd Berger and produced by Kevin Brennan, Jeff Grace, and Brett D. Thompson, and stars Sherilyn Fenn, Blaise Miller, Suzanne May, Jeff Grace, Kevin Brennan, Todd Berger, Monika Jolly, James Jolly, and John Landis. 2009, DV, Color, 96 minutes.

EYE OF THE SANDMAN is a production of Split Pillow. It was directed by Dennis Belogorsky, MT Cozzola, and Jeffrey McHale, written by MT Cozzola, and produced by David J. Evans V and Jamye Graham, and stars Jeanene Beauregard, Allan Aquino, Errol McLendon, Dave Belden, Megan Keach, Aemilia Scott, and Andrew Yearick. 2009, DV, Color, 74 minutes.

SEVEN SIGNS: MUSIC, MYTH, AND THE AMERICAN SOUTH is a production of Colonel Films, Milk Products Media, JuddFilms, and TuckyWood Productions. It was directed by J.D. Wilkes and produced by J.D. Wilkes, Todd Tue, Blake Judd, and Jacob Ennis, and features Slim Cessna, Jay Munly, John Akin, Scott Biram, and Professor Peter Fosl. 2008, DV, Color, 52 minutes.

~~~~~

~~~~~

Michelle Kaffko is a Chicago resident and life-long Midwesterner with a B.S. in Cinema Studies and film theory. She is an independent filmmaker and photographer. She can be reached at michelle [at] findmichelle [dot] com.

“A Knife in a Gun Fight” no. 3 © 2009 Michelle Kaffko.

Split Pillow board members photo @ Jason Stephens’ residence

© 2009 Michelle Kaffko.

Used with permission.

CUBlog edit © 2009 Jason Pankoke

Bankroll graphic © Michael Wiese Productions

Click to purchase!

THE SCENESTERS graphics © Vacationeer Productions

Click to visit the official site!

EYE OF THE SANDMAN graphics © Split Pillow

Click to visit the official site!

SEVEN SIGNS graphics © Milk Products Media

Click to visit the official site!